- Home

- Shari Arnold

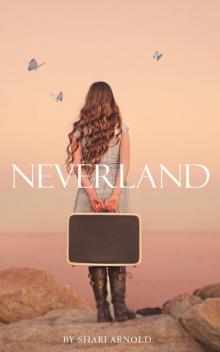

Neverland

Neverland Read online

Also by Shari Arnold

KATE TRIUMPH

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, transmitted, or stored in an information retrieval system in any form or by any means, graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, taping, and recording without prior written permission from the publisher.

Copyright © 2015 Shari Arnold

This story is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and events are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

ISBN 9781508846482

Published by CreateSpace

To my very own Nana and her little brother, Emerson. I love you both dearly.

PART ONE

Odd things happen to all of us on our way through life without our noticing for a time that they have happened.

-— J.M. Barrie

Peter and Wendy

CHAPTER ONE

It’s just before dinnertime at the Seattle Children’s Hospital. Beef Stroganoff tonight. My sister’s favorite. I’m almost to the best part of Peter Pan — you know, where Wendy has just walked the plank and everyone on the ship is freaking out because there was no splash.

I pause for a moment and smile down at the newest addition to story hour. She smiles back. She’s still clutching her mother’s hand like it’s her lifeline, but she’s no longer hiding behind her. So that’s something. Her light-colored eyebrows and pale skin make me think she was a blonde before they shaved her head and injected her with poison. And the light in her mother’s eyes tells me there’s still hope.

“Where’s Wendy?” Jilly calls out even though she’s heard this story countless times before. The way the children are watching me you’d think it was the first time I’d read it to them. Jilly claps loudly and the IV attached to her right hand sways back and forth as if it shares her excitement.

“Well,” I say, drawing out the word. “What do you think happened to her?”

“Peter Pan!” the children chorus, all except Gerald. He’s sitting in his mom’s lap, eyeing me as if I’m foolish for asking this question.

“She’s dead. Drowned in the water,” he says, before his mom shushes him. Lately Gerald has developed a fascination with death. From what I hear some of the other parents find it off-putting.

“No! She’s not dead!” Jilly says in her most authoritative voice. “It’s Peter Pan. He’s saved her.”

And I laugh. Of course it is. Who else would it be?

I turn the book around to show them the illustrations and they collectively lean in close. A handful of the kids are sitting on the floor near my feet while the few who are too sick to leave their beds create a perimeter around us. But every last one of them is locked on, waiting for the happy ending. Even Gerald. Their eyes are wide and curious, and I love that. If I focus on their eyes I can forget the disease each one carries around like a nametag. I can forget that statistics rule their lives. I used to do this with my sister, Jenna, and near the end she would put her face right up to mine so that our noses were touching and say, “Can you see me, Livy?” and I’d say, “Always.”

Sometimes when I close my eyes I still see her: honey and peach-colored and never without a half-eaten candy necklace hanging around her neck. At least that’s how she used to be. But most of the time I have to pull out a photograph and remind myself of what her smile looked like, how her mouth was a mix of permanent and baby teeth. And how she had this funny little birthmark near her right temple that was shaped like an elephant, and when asked about it she would claim it was a tattoo because it would make my mother cringe and my father chuckle. After only four months of her being gone I have to rely on a photograph to remember how her eyebrows were so blonde you couldn’t see them unless you looked really close. And how her laughter was so loud and freeing that it would usually catch the attention of perfect strangers on the street.

“Livy? What happened to Wendy?” Jilly says, bringing me back to the present. I turn the book around and flip to the next page.

“Tick, tock. Tick tock,” I read and the children squeal: “It’s the crocodile!”

I stop reading long enough to glance up. I wish I could capture their joy and hold it in my pocket, bringing it out on those days when even the promise of a new toy can’t drudge up a smile. “This is what happiness sounds like,” I’d tell them as if a simple reminder is all they need to feel better.

“What happens next?” Gerald calls out, and then thinking better of it he rolls his eyes and says, “not that I’m interested.”

I’m about to answer when I notice him. That same boy. The one I occasionally see when no one else is paying attention. He’s standing just inside the doorway wearing dark jeans and a hoodie. His arms are folded, his ankles crossed. He’s lounging while standing up. And when our eyes meet he grins. Who is he? I know he doesn’t belong to any of the children here because I’ve asked. In fact, no one on this floor seems to claim him at all. But nevertheless, there he is. Watching me.

“Are you going to finish, Livy?” Gerald asks with his sandpaper voice. “You know, some of us aren’t going to live forever.”

The boy in the doorway raises an eyebrow as if he too is wondering if I’m going to finish. But he isn’t a boy. He’s perhaps a year or two older than me, which would make him more adult than boy. But there’s something about his smile that makes him appear younger. More youthful.

“Of course I’m going to finish,” I answer, except now I’m nervous. My hand shakes when I turn the page and even though I will myself not to, I clear my throat.

“The sound of ticking is coming from the water down below. Tick. Tick. Tick.” I take a breath while the children continue to hold theirs. And he’s watching me. Still watching me.

I finish the story just as Nurse Maria strolls in to announce that it’s time for dinner. But the children don’t want food. They want Peter Pan. The few who entered the playroom on their own two feet are now flying about with their arms extended and their pajamas flapping. I smile while I watch them. They look so free, so happy. For a moment I forget their troubles, just like they have.

“Again! Again!” they cry. “Read it again!” Even little Sammy, who rarely makes any noise at all, has joined in. Sometimes I don’t even hear his footsteps before he tugs on my shirt to get my attention.

“Please, Livy!” Jilly begs from her hospital bed and I can’t look at her when I explain that story hour is over. I never want to be the one to tell her no. She hears it enough.

Nurse Maria makes airplane noises as she pushes Jilly’s bed toward the doorway.

“Don’t leave without saying goodbye,” Jilly calls out, her head arched back so she can see me.

“Never,” I say. Just like I always do.

“See you tomorrow, Livy,” Gerald squeaks out and his skinny arms wrap around me. He blushes when I kiss his cheek and it makes me want to hold him tighter, longer. “Try not to die tonight,” he says. “It’s dangerous out there.”

“I’ll be careful,” I say and playfully swat at his hair.

When I glance toward the doorway the mysterious boy is gone.

Jilly is sitting up in her hospital bed, her small body only half filling it, when I stroll in. She’s eating chocolate pudding and applesauce — her bites small and staggered — and drinking from her favorite Princess Jasmine cup. No Stroganoff for her tonight.

“Livy!” she calls out and pats the side of her bed.

I tuck myself in next to her and she turns her face on the pillow so that our eyes are aligned.

“I miss Jenna,” she says and I nod. Jilly is one of the few people who still want to talk about my sister. Most don’t bring her up at all or change the su

bject if she slips into a conversation. I’ve found that death makes people uncomfortable, while the death of a child clears the room altogether. And that’s okay. To be honest, it’s not something I want to talk about either. But when I’m at the hospital with the kids everything is different. I’m different. I’m strong Livy, unshakable Livy. I talk about pain and death and how it feels to lose someone you care about, someone you didn’t have enough time to get to know. Because the people I meet in the hospital are still living it; they’re weeks or months away from being me. They come here with hope and if they’re one of the lucky ones they’ll leave with it. They’re not like the rest of the world: too afraid to hear the truth when they ask, “how are you doing, Livy?”

“What do you miss?” I whisper to Jilly now. We’re close to the end of visiting hours and even though there isn’t a doctor or a nurse in this section of the hospital that would reprimand her for being awake — for being alive — I don’t want to keep any of the other children up.

“I miss playing dolls with her and the stories she used to tell.” Jilly’s eyes take on a pleading look and I know what she’s about to ask. She is never satisfied with just one story. She always wants more. More cake, more ice cream. More time with me.

“Which one do you want to hear?”

“The Twelve Dancing Princesses,” she replies and I smile. Of course she’d pick that one. It was Jenna’s favorite. “Will you tell me the story, Livy? Just until Grandma gets here?”

Jilly’s grandma, Eliza, rarely makes it to the hospital before bedtime on Wednesday nights. She works clear across town and has to skip lunch just to leave a few minutes early in hopes of making it here before Jilly has fallen asleep.

“Please?” Jilly begs and I take a deep breath.

“Sure,” I say, even though each time I tell this story it feels like I’m losing my sister all over again.

“Don’t forget the dancing scenes,” Jilly says. “Jenna used to stop and act them out.”

Of course she did. My sister danced everywhere she went up until the end when her little body just couldn’t do it any longer. That’s when it really hits you. When your six-year-old sister, the one who would barge into your room first thing every morning to jump on your bed, can’t hold herself up.

Jilly pulls the blanket up around her chin. All I can see are her wide brown eyes.

“I’m ready,” she says, her voice muffled.

“There was a king who had twelve beautiful daughters,” I begin and those brown eyes of hers crinkle in the corners just like Jenna’s used to each time she’d smile.

I’m halfway through the story when Jilly’s grandma rushes into the room. And I’m surprised, just like I always am, how fast she moves for a woman in her seventies. It’s funny how love will do that to you.

“Did I make it?” she says out of breath.

One look at Jilly and she has her answer. Jilly’s eyes fluttered shut about five minutes ago, just before the soldier arrived at the palace.

“When did they give her the medicine?” Eliza asks. She pulls off her coat and tosses it onto a chair in the corner, along with her purse.

“With dinner,” I say sliding off the bed to make room for Jilly’s grandmother.

“Any improvements today?” she asks, her eyes hopeful.

I look away. “Not much.”

“Goodnight, Jilly,” I whisper, but she can’t hear me. She’s been dragged down into the dark and dreamless world of undisturbed sleep, the kind that only heavy painkillers can produce.

“Goodnight Eliza,” I say and Jilly’s grandma takes her eyes off Jilly just long enough to give me a smile.

“See you tomorrow,” she says and I nod, even though it wasn’t a question.

I make my way down the hallway toward the stairs. Near the end of the hallway I can hear Sammy’s parents beginning their nightly prayer from inside his room. With their hands they form a circle that includes Sammy and Sammy’s favorite stuffed bear, Brown. I bow my head and join in even though I’m pretty sure it won’t help. God doesn’t save children around here. Sometimes it feels as if he’s collecting them.

Sammy’s parents murmur, “Amen,” and I catch a flash of movement out of the corner of my eye. Someone in a dark hoodie has slipped inside the stairwell. And since I’m going that way anyway, I follow him.

CHAPTER TWO

I pull open the door that leads to the stairwell and catch a flicker of jeans right before they hop the railing, landing on the steps below. I’m not sure what I’m doing, or what I’ll do if I catch up with him. But I want to know who he is. For weeks now I’ve noticed him; he shows up out of nowhere and sticks around to listen to the stories I tell. And he’s always alone.

I sprint down the first flight, not brave enough to jump the railing like he did — show-off. But when I make it to the bottom floor I find I’m the only person in the lobby wearing jeans and a hoodie. I pause for a minute, looking around, but the boy with the smile is gone. He’s managed to disappear again.

Outside the night is silent and wet. Typical. When I was younger, I asked my parents why it’s always raining here. My mom answered, “Seattle is so beautiful even the clouds can’t bear to leave it,” while my father said, “After a while you don’t notice it, Livy. Just you wait.”

I’m seventeen now, and still waiting.

I pull the hood of my raincoat up and over my strawberry-blonde hair, the hair I inherited from my father, who inherited it from his mother who brought it to the US from Ireland where there are many strawberry-blonde relatives running about. I’ve never actually been there, but I imagine they’re also cursed with pale skin and a dusting of freckles on the bridge of their noses. My father used to describe it as being sun-kissed until the day Jenna overheard and got upset, wondering why the sun hadn’t kissed her too. The only way I got her to stop crying was to promise that the next time the sun came out we would go and ask it for a kiss. Thankfully when the sun finally did come out (three weeks later) she’d forgotten all about it.

I dodge the puddles in the parking lot even though I’m wearing rain boots. I hate being wet. I hate how you still feel wet long after you’ve come inside from the rain, as if the moisture has moved past your skin and into your bones. Some days it’s like I’ll never feel dry again.

There’s a large puddle next to the driver’s side door of my car and I think about what Jenna would do if she were here. Splash, of course. Stomp that puddle until the both of us were covered in it. Jenna never shared in my distaste for being cold and wet.

I’m reminded of one of our many visits to Alki Beach. I was standing on the boardwalk and Jenna was holding my hand. She was almost five. Each step I took she jumped, nearly pulling my arm from its socket. Even when there weren’t any puddles on the ground she stomped. “I’m practicing,” she’d explain.

“Chocolate and rainbow and mint,” she sang. “And bubblegum.”

She jumped again just as I was about to step off the curb and I stumbled slightly.

“Four scoops?” I said. “Do you really think mom will let you have four scoops?”

“But I can’t decide!” Her grip on my hand tightened and I squeezed back.

“I like bubblegum,” I said. “And I like rainbow.”

“They’re your favorite!” Her blue eyes turned up to me, her smile displaying the gap left behind from the two bottom teeth she’d recently lost.

“My favorite and my best,” I said quoting her all-time favorite show, Charlie and Lola.

Jenna giggled and just like that it was decided. We’d be sharing ice cream that night.

Sometimes the memories crash against me like a tidal wave and sometimes they arrive as a feeling that hangs about all day. And even though I know it’s good to remember Jenna, sometimes I wish I could forget, slip the memories into a large box and bury them in the ground for someone else to find. “Here lie my memories of Jenna Cloud. May you love her as much as I did, without the pain of having lost her.”

&n

bsp; My parents and I live in an apartment building, which isn’t so unusual in Seattle. What is unusual is that we live on the entire top floor of a building my father designed. Marty, the doorman asks me how my night was and how Jilly is doing and I tell him she’s strong and determined while he nods his head and forces a smile. We both know what I’m not saying: if Jilly doesn’t find a match for her bone marrow transplant she probably won’t make it to her seventh birthday. In my mind seven is the lucky number. Jenna never made it to seven. I’m convinced that if Jilly can she’ll be fine. She’ll begin to collect birthdays the way she and Jenna used to collect sea glass. Her birthdays will all knock around inside a Ziploc bag that gets heavier each time we visit the Sound.

With a soft ping the elevator opens. My mother’s back is to me but when she hears the elevator doors she turns around and greets me with a close-lipped smile. This smile paired with her narrowed blue eyes is her working face, the one she wears pretty much always lately. It’s the same look she gives me every time she asks if I’d like to visit with Dr. Roberts again. “He can help you work through it,” she says, as if sadness is a math equation, as if instead of a prescription he can write out a simple formula that will help me when I’m as gray as the Seattle skyline.

But the truth is I don’t need to see a doctor. I cried. I still cry. Crying is normal. I’m normal, unlike my mother who controls her emotions as if they’re an outfit she can slip on and off.

“There’s lasagna in the oven and garlic bread in the toaster,” she says now, while the many people who help manage her career continue to talk around her. Most days I feel as if I’ve been dumped right onto another page from my mother’s unwritten biography, entitled, Mary Cloud, Washington State Senator. Not that I’d even make it as a supporting character. If anything I’d be forever italicized in the footnotes as Olivia Cloud, first born. Even though for the rest of my life I’ll be an only child.

Neverland

Neverland